During the presentations at the Workshop on Adaptive Case Management (ACM) on Monday, there was a growing question about the models: Not just how models should be constructed, but whether we should be using models at all. These ended up forming a major discussion at the end of the day, and even into the rest of the week, culminating with the final keynote questioning our obsession with models in BPM. This is my take on the main positions in the debate.

Every presentation at the workshop dealt with modeling: (1) can CMMN model what is needed by ACM, (2) comparison of 5 different modeling approaches, (3) a way to model variants in process, (4) consistency checking of models, (5) modeling crisis scenarios with state charts, (6) using semantic web to compare models, (7) modeling based on speech acts, (8) more consistency checking within models, and (9) using viable system model for ACM.

It is not just this workshop. I have been seeing this everywhere. Lloyd Duggan gave a mini course on case management where he said that the difference is that BPM uses BPMN and case management uses CMMN. If you read the papers, you see statements like: “We needed to model, so we chose CMMN.” There are comparisons between approaches based on comparing how models are built. There is a build-in assumption that to do anything we start with a model.

Questioning The Value of Modeling

The assumption is a blind spot: If it is true that modeling is effective, we should be able to show that through the use of a model we allow the user to get more done than when a model is not used. However, this question is rarely, if ever, asked. The second presentation compared the expressibility of various modeling techniques, however the actual advantage of modeling was never demonstrated. Almost no research is done comparing cases where a model is used, to a control case where a model is not used.

A Convenient Crutch

One might suspect that models are foremost in research, because they are quite a bit easier to study than real office behavior. Interview some people, make a model, and then put the model under a microscope. You can experiment with the model, find the ways that it fails. Two of the talks were about ways to find inconsistencies within a given model, to avoid deadlock type situations in the model. However, these deadlocks have nothing to do with the behavior of the actual workers in the office, it is simply a flaw in the model.

Through all of this, we lose sight of our real goal: making workers more effective. We really do need to do controlled studies: consider a set of offices, measure the performance, then give one set of offices use the ACM technique, while another set continues operating manually. Measure the increase in performance. We need to keep our eyes on actual knowledge workers productivity, and not get distracted by our attractive technical developments.

Who is Modeling?

We need to be clear about who is modeling. When talking of an ACM system, we all know that such a system is built from software. That software might be modeled. The issue is not whether the programmer of the system uses a model to make the software. That would be a question of the use of modeling in software development — a completely separate issue from the use of modeling in ACM by the knowledge workers. When an approach to ACM is presented as “providing modeling” we know that means modeling by the knowledge worker, or by someone close to the knowledge worker, as part of the knowledge work. When we talk about modeling being “part of” the ACM System, it means that modeling capability is presented as part of the features for the intended users of the system — not the programmers who make the system. I know these lines are blurred somewhat in some systems that can be “customized” by programmer. Still, lets keep this modeling discussion about those models created by the knowledge workers themselves. For example, a law office, we consider the modeling done by lawyers, even when only 10% of the lawyers actually make models, but lets not consider modeling done by someone who only does modeling,a nd never does any law.

An Example of a Non-modeling Approach

One of the best examples of a system that supports extensive, complex knowledge work is Git Hub. Software product designers and programmers have a very complex, knowledge intensive task to accomplish. Git Hub offers a simple, elegant way to coordinate this work:

- issues can be logged by anyone at any time. The issue describes the problem or the work to be done.

- team members can discuss any issue using a chain of comments, either asking questions of clarification, or stating positions.

- issues can be tagged and classified in different categories, such as bug, feature, enhancement, urgent, ignore, and others.

- issues can be grouped into milestones, which have an intended release date.

- programmers can focus on all the issues in a milestone, marking off issues as the work implied by the issue is completed. Everyone on the team can be aware of the status of the milestone.

- Milestones can be adjusted and replanned by moving issues in and out of the molestone.

That is it. Simple and effective. Used effectively by thousands of projects today. There is no modeling capability. There is no automation of the knowledge worker tasks. There is no need for a modeling language at all. And it works.

Another example I have used in the past is Easy Chair, which is a system used to collect, review, and judge papers submitted to a conference. This system is used by hundreds if not thousands of conferences every year, and most academics are familiar with it. It allows knowledge workers to get their work done — very effectively by all accounts — but it offers no modeling capabilities at all.

Both of these are software systems, so one might assume that the programmers who developed them used models. We don’t care. This discussion is not about modeling in software engineering, but modeling by the knowledge worker as part of doing knowledge work.

Everything is a Model

One particular rat hole that the discussion kept going down is the position that anything you do to customize is a model. For example, in Git Hub you can specify the labels that are used for categorization: I might have 5 varying levels of urgency, while someone else might only have three. In Easy Chair you can decide whether abstracts can be sent in ahead of the submission, or whether the full submission must be given at once. These changes effect the way that the users must behave with the system.

In some purist technical way, any setting that one person makes effecting another is modeling. These trivial mechanisms are not what most people mean by modeling. I think we know by modeling, we mean some flexible, abstract, general purpose representation of the work being done. When we say the work can be modeled, we don’t mean that there is a check-box somewhere that directs work differently. Or a label.

The true gray-area is that of checklists. A checklist is a general purpose representation of a collection of tasks. One might argue that this is modeling. For example, grouping the issues into a milestone in Git Hub, is modeling the work to be done for that milestone. No! I am not buying it. The difficulty in modeling has to do with a certain level of abstraction. Checklists are concrete. If we want to discuss the merits of modeling, we must be talking of models that are more abstract than a checklist.

For What Purpose?

My stated position was that we must consider and measure the benefit of a model. WE can not assume that it offers a benefit, and as you can see there are good examples of knowledge work systems that require no modeling by the knowledge workers. They offer no possibility for it, and there does not appear to be any problem.

Models could be useful for a purpose. For example, a model of the work can be very important in predictive analysis, where you use patterns of behavior together with emerging workload, to predict how many resources you will need. A call center wants to make sure they have enough knowledge workers available on days when load is expected to peak. Presentation #5 was about emergency response, and having a model to simulate potential scenarios before an emergency can be critical. It can also be useful to take inputs and warn about potential problems as the emergency is unfolding. A model can be used in numerous simulation situations. Some of these models would be implemented by a specialist who does only models: for example the person who makes a model to predict problems in a flood, might not be an actual emergency rescue worker. The question still remains whether a system to support emergency responders needs modeling capabilities.

If we include modeling in an ACM System, then we should be very clear what the purpose and goal of such modeling is. We should then not only show that it achieves this goal, but that also, as a result of the modeling, the work of the actual knowledge workers is made more effective.

The rest of BPM as well

Outside of the workshop, we saw a lot of the same sentiment: we are too hung up on modeling. Far too many papers assume modeling, and then study the model. Studies of model correctness constraints are about assuring that certain modeling rules are not broken — not necessarily whether the business that uses the model improves from it.

Leon Osterweil, a hero in the 1990s in the software process model domain, whose work I have cited many times, attended the conference and participated on a panel about agile BPM. However, it is somewhat ironic and humbling to realize that in the software development space, real progress has been made not by developing an elaborate executable process model, but instead by going the other way to agile approaches, such as SCRUM. SCUM has a method to be sure: two week sprints, daily stand-up meetings, visible status, develop test before developing the code, but these are less like automated processes, and more like simple patterns of interactions on which programmers manually create the software. Git Hub does a brilliant job of coordinating developers work, without having any readily apparent enforcement of something you might call a process model.

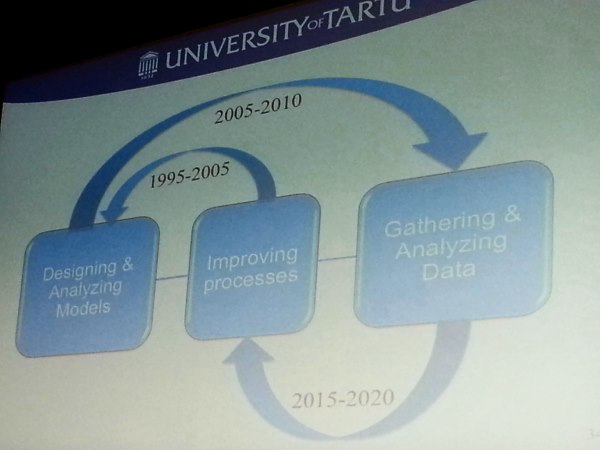

Marlon Dumas gave the closing keynote for the BPM Conference including a history of the BPM field from 1990 to date. He also decried the focus we give on models: measuring models, improving models, etc. to the exclusion of knowing whether we are actually creating the business. He showed how at different times we moved from studying process, to studying models, to studying analytics. He urged a change in culture for the papers next year and beyond. Modeling and analytics are tools to use to improve a business process, but they are not themselves the business process. The model should not be the focus of the research. Instead, we should focus on returning to study the actual business process, the actual work being done, and show how we can make the business more effective, possibly with the use of models.

Marlon Dumas gave the closing keynote for the BPM Conference including a history of the BPM field from 1990 to date. He also decried the focus we give on models: measuring models, improving models, etc. to the exclusion of knowing whether we are actually creating the business. He showed how at different times we moved from studying process, to studying models, to studying analytics. He urged a change in culture for the papers next year and beyond. Modeling and analytics are tools to use to improve a business process, but they are not themselves the business process. The model should not be the focus of the research. Instead, we should focus on returning to study the actual business process, the actual work being done, and show how we can make the business more effective, possibly with the use of models.No Model is a Good Model

I think a whole lot more can be done to support knowledge workers without the need for modeling. We need to study those. Modeling might be useful in situations, but we should be clear about the purpose of that modeling, and we should measure whether the model is actually effective in improving the work of knowledge workers. We should not be blinded by the assumption that modeling is a necessary part of ACM.

0 comments:

Post a Comment